By Shoji Hashimoto

A ceremonial photo taken in commemoration of the erection of the tower. Author, in the back on the right behind his daughter who is currently a junior in college.

Summer eight years ago, my Amazon observation tower was finally complete. The tower was an essential part of my life work to expose the mode of life of Agrias butterfly in the Amazon rainforest. At precisely the same time, however, I fell a prey like a hornworm stung and paralyzed by a wasp! To put it plainly, some wicked ones in the Amazon falsely accused me of "smuggling insects" out of the area, and I was deprived of my tower, while the authorities treated me like a criminal. Now, I am off the hook and have got my tower back, thanks to persistent support from so many people on the right side of the law. So, I feel it is my responsibility to give a full account of the eight years' struggle that I went through.

A little past two o'clock on the afternoon of August 16, 2001, THEY sprung up before my eyes in the jungle.

With a bucketful of fermenting banana pieces in my left hand and a butterfly net in my right, I stood motionless, watching four men defiling toward me.

The lead man --- a soldier type, middle-aged well-set white man --- held a .38 caliber Brazilian revolver in his right hand, and in his left, a black leather pocketbook with a telling gold badge. He trained both of those at me and said "Policia Federal [Federal police]." The rest of the crew consisted of an equally well-set hard-featured fellow in a colorful short-sleeved shirt, a slightly smaller guy who was apparently a bureaucrat, and a young man with a thin smile and a huge TV camera on his shoulder.

"Hashimoto?" asked the gun-wielding man.

"Sim [Yes]," I answered, wondering.

As sure as anything, my name was Shoji Hashimoto, a first-generation Japanese immigrant and head of the Amazon Natural Science Museum. Though bandits were not uncommon around here in Brazil, I doubted that these guys were that bunch. But I wondered what kind of business it was that brought the quartet of two servicemen, a bureaucrat and a media guy all the way to this jungle 40 kilometers away from the city of Manaus.

They needed me, not the jungle, of course.

Recognizing that this 166-centimeter-tall Oriental holding rotten banana and a butterfly net in his hands had no intension of resistance, the lead man finally put his pistol back into the holster on his waist and asked another question, "Porque esta aqui [What are you doing down here]?" Good thing that I had adequate Portuguese language ability to comprehend such a simple question."Pesquisa [research]," I replied.

The hard look remained in the eyes of the solider type, and then he jabbered something --- something incomprehensible to me. After having spent 26 years in Brazil, I had a command of Portuguese barely good enough to impress tourists, but that was about as far as I could go. Actually I was unskilled at the language. Still, I sensed that this was no joke. With each passing moment, I became increasingly spitless.

In October 1999, I had brought into the jungle a radio tower manufactured by Aichi Tower Industry Co., Ltd. of Japan, the world's best radio-tower manufacturer, on which I had spent several tens of thousand dollars and which I had modified to suit for insect observation in the jungle. As a matter of course, the tower entered Brazil legally, and all the papers were in order. Unlike the conventional observation towers, this one only required a footprint of one meter by one meter, and yet was capable of telescopically rising up to a height of 40 meters above the ground by an electric motor. It was nothing like what you would normally expect to find at power transmission lines, such as one having a huge footprint of, say, five meters by five meters that would require the felling of trees and end up scaring the insects away from the immediate vicinity.

The tower would allow me to make sweeping observations --- i.e. not just two-dimensional but three-dimensional --- of the pristine environment at higher sections of trees and their canopies in Amazonian rainforest. Even a relatively short arboreal observation (let's say, a week) on the tower might allow for the finding of one or two new varieties of butterflies. It was a tower of insect buffs' dream!

It had been a year since the erection of the tower when the four guys barged into the site. I and Nakashita --- my friend/assistant --- had just gotten through with the required tower maintenance work which started around ten o'clock in the morning, and were replacing insect baits along the way.

My reply "Pesquisa" obviously didn't convince the middle-aged man who identified himself as a federal police officer. He badgered me with questions (well, I guess they were questions) but I couldn't understand what he was saying. All that passed my lips was "Não entendo [I don't understand]." Giving up on my linguistic ability, they turned to Nakashita and fired questions at him. They were flogging a dead horse, because Nakashita had volunteered to apprentice himself to an insect buff (that is me) here in Brazil only a few years before, ditching his job as a chief officer of a 100,000-ton class oil tanker. Hence, Portuguese was Greek to him --- more so than to me. The young camera man began shooting my face with his video TV camera without my permission, while with his thin smile, he kept hammering away, "Captura?", "Captura?" What a rude bugger! I remembered watching a TV engineer acting just like him in Bruce Willis' movie, Die Hard.

I repeated, “Não entendo.” I didn’t understand what he was saying, honestly.

I was lucky that I didn’t really cotton on to what was meant by the word “captura” at that time. I was not good at foreign languages, but still would never utter “yes, yes” in a blind way. From my 35 years of seasoned experience in Latin America, I was well aware of the danger of such a temporizing reply. And cloaking yourself in an ambiguous smile would be absolutely out of the question under such circumstances. Not a small number of Japanese immigrants had been stripped down to the bone by rogues like flesh-devouring piranhas or candirus (toothpick fish) just because they said “yes” unawares.

After about 30 minutes of exchange of mostly incomprehensible words with me, they seemed to have eventually realized that we were getting nowhere; so they said they were taking me to the federal police station. In this fruitless exchange, I heard the expression “biopirataria” several times. “Bio” is the same as “bio” as in biology, and “pirataria” means “piracy” in English, with which even I was familiar because the word was a regular player in news reports on police revelations of pirated CD’s and DVD’s, for example.

So, “biopirataria” literally means “biopiracy.” I had a hunch that there must have been a gross misunderstanding of whatever was alleged to be my fault. I thought that such a misconception should be readily removed if I sat down and explained at the police station. But that wasn’t so. It would turn out to be me, not the police, who was laboring under a misapprehension. Thus began my “Eight Years’ War” with THEM.

[TOP]

In 1993, Brazil put tough restrictions on insect and plant collecting within the country because the government became aware that the country’s biologic resources, which had gone unchecked theretofore, were potential gold mines for biotechnology. In the Amazon, therefore, nobody was allowed to collect insects, worms or plants whatsoever without a special permit. Offenders were subject to a prison sentence. Those collectors who thought they could lick the system if the amount of pickings was small would most likely get caught red-handed at the airport and end up in prison.

The high-performance fluoroscopes installed at Brazil’s international airports are capable of detecting water in the body of an insect of mere 5 millimeters in length, let alone more susceptible metallic articles, and indicating the presence of contraband in red color on a display. The impartial clairvoyant device would not let the smallest bug slid by, even when it was wrapped in tissue paper and tucked away deep in one’s pocket. So, on my website, as well as in my responses to numerous inquiries from Japan, I’ve been repeatedly blowing the whistle for the past ten years against any attempt to do something you’d regret.

The butterfly net I was carrying in the jungle was a catching tool for temporarily capturing a butterfly that would be shortly released after I mounted a tiny transmitter on its body. For this purpose, I had visited Japan in spring that year to buy a telemetry system comprising micro-transmitters and a receiver. I’m sure you are familiar with those tiny chips for wireless communication that are commonly used in documentary films on small animals. While beetles and small lizards could be somehow mounted with such a transmitter, I was inwardly proud that there was nobody but me who had such a wild idea of having a butterfly shoulder a wireless chip. I was learning by trial and error how to make my exciting plan viable; as you would expect, the cargo was too heavy by all odds for the frail airborne creature. It had been my lifelong dream to throw light on the mode of life of Agrias butterflies using a high-rise tower and a telemetry system, and that was what had initially kicked me out into the Amazon as an immigrant in 1975. I firmly believed that with the aid of a tower and a telemetry system, my dream would come true soon.

The federal police bunch crammed me, and Nakashita, into their car and headed for their headquarters in Manaus. We were not under arrest but still being taken in for questioning. Nobody talked in the car. I was totally clueless about why they were raising a clamor about “biopirataria”. Surely I had placed an insect cage in the jungle where my tower was erected. Being trapped in it, however, was a single bug known as clown beetle or hister beetle which was a fingernail-sized bug ubiquitous in Manaus, and which obviously blundered into the cage on its own. You can say that the social standing of this bug in this part of the country is probably comparable to that of a housefly in Japan. Can they penalize me just for possessing an insect cage with such an ordinary bug sitting therein? I had no idea of what these guys were up to. While I was being wrapped in serene contemplation of the unknowability of the universe, the wide expanse of the huge one-storied white building of the federal police headquarters in the immediate vicinity of Manaus Airport gradually came into sight.

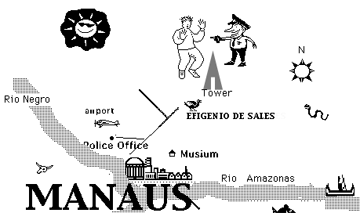

Manaus is the capital of the state of Amazonas covering an area eight times larger than the total land area of Japan. Nonetheless, the tropical rainforest city is poorly furnished with tourist attractions. Those tourists from all over the world visiting here in hope of getting to see many exotic places wouldn’t know what to do with their time once they have visited the Amazon Theater (Opera House), which is a reminder of the rubber boom around the late-19th century, and the Amazon Natural Science Museum, which I founded and constructed some twenty years ago, and in addition to them, perhaps, the central market where all kinds of agricultural produces and fishery products from the Amazon basin are piled up.

Yet the city had grown to be one of the 10 largest cities in Brazil by the beginning of the 21st century from a medium-sized city with a population of 600,000 when I first set my foot here as an immigrant; the growth of the city was primarily due to the success of a free economic zone which was instituted in 1967 to attract more manufacturing businesses from the leading industrialized countries with a view to promoting regional development. The area where I opened my museum was a suburb of Manaus 20 years ago but has been swamped ever since by waves of urbanization to such an extent that the old growth in the museum’s garden has been designated as one of the few treasurable virgin forests left within the municipal district of this industiral boom town with a population of 1.8 million.

The headquarters of the federal police, which was modeled after the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) of the United States, was located in a residential district across the city from my museum. Brazil’s federal police was in charge of major crimes involving interstate activities and of immigration control on aliens, in addition to environmental crimes. The name of the man who took me here turned out to be Helder, and apparently he was a squad leader of Section V that was in charge of cases related to protection of the natural environment. When we arrived at the headquarters after an hour-long drive, it was almost 5 o’clock in the afternoon.

Both Nakashita and I were whistled to an interrogation room where we went through a stereotyped course of personal identification by way of such questions as what my name was, where I was born, and when I came to Brazil, as well as my birth date and present domicile. In the meantime, they went so far as to bring on not only vice president of my museum, Ishizawa, but my wife as well. Lots of plastic cases containing butterflies wrapped in paper that they had confiscated from my museum were unloaded from a truck and displayed on the floor of a corridor. Ishizawa was proficient in Portuguese for he had emigrated with his parents from Yamagata prefecture, Japan when he was seven years old. “Looks like we’re suspected of smuggling insects,” Ishizawa informed me in Japanese. It was as I suspected. But all the specimens in the confiscated cabinets were the ones that I had collected for the opening of my museum many years before. Collecting of insects back in those days was not at all against the law. It shouldn’t constitute a crime of “biopirataria.” Having come to that conclusion, my gray cells were eventually awakening from dormancy.

But I was wrong. In hindsight I was so far from realizing the true severity of the situation then.

About an hour and a half later at around 6:30 PM, Consul General Kobayashi came rushing to us with his interpreter. It was a great surprise, and relief, too. Also, a Brazilian lawyer showed up. The Consul General had already been well informed --- far more than I was; he knew that I was suspected of “insect smuggling”. I was told that this incident had topped the 6 o’clock TV news, about which I had no way of knowing, of course. Later I learned that watching the TV news, a friend of mine at the Japanese Chamber of Commerce in Manaus was extremely concerned that I might be convicted on trumpeted charges in this country, so he wasted no time in calling the Consul General who in turn swung into action to hire the lawyer. The Consul General was so considerate that he arranged to leave one of the consular officers as an interpreter for me. It was a real help, indeed.

Later I also discovered that the federal police would have by all means put me under arrest at the headquarters had the Consul General and the lawyer not been present there.

A full-fledged questioning began at 7 o’clock. Here a new character came into the picture --- a senior “delegado” [chief investigator] in command of investigations of my case. He was a fat-bellied, dark-skinned sedentary type by the name of Nivardo. His interrogations were anticlimactic. Setting before me a bill of receipt (which they seized from my museum) for a stuffed specimen of pirarucu I had sold before, he asked an absurd question, “The amount written here is too much. You must have used the specimen to stash contraband insects for smuggling, huh?”

The pirarucu was a species listed in Appendix II of the Washington Convention [officially called ‘Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora’ (CITES)], which meant that international trade of specimens of the species for commercial purposes was banned, while their export for academic research purposes was permitted in licensed circumstances. As a matter of course, the specimen of pirarucu corresponding to the receipt was the one I had exported with a formal license. Above all, the destination for export was a Spanish aquarium. The delegado’s allegation that ‘the high price might well have represented smuggling of some insects stuffed therein’ clearly suggested complete absence of evidence. I argued him down, saying, “Nobody in the Amazon but me had the skill of making a decent specimen of pirarucu that is over two meters in length. The reason why it fetched a good price was because the quality of my specimen was superb, just like Honda motorcycles. You see? And what’s the point of selling insects to an aquarium in the first place? If you do a little research, you’ll know that what I’m telling you is true.” The presence of the competent interpreter from the consular office really boosted my confidence.

The questioning was a slow-moving process, because every thing Nivardo said had to be translated into Japanese and my response to his question back into Portuguese. A single set of question and answer, which would have taken less than one minute between two persons sharing a same language, took as long as 5 to 10 minutes. Worse yet, Nivardo asked repetitive questions every other 30 minutes. Perhaps he believed it was a smart way of conducting an interrogation. Naturally, Nirvado’s repetitive questions were met with the same responses from me every time. The clock was still ticking. In the meantime, Nirvado’s team dug in home-delivered pizzas. Nakashita and I were offered nothing, of course. So, we had no alternative but to munch on cold rice balls containing bits of pickled plum, which were leftovers from our lunch.

Earlier on that day the federal police had mobilized about 15 personnel to search my museum, home and a couple of other places. They carted off boxes of unclassified insect specimens, video cameras, PC’s, documents and files from the museum as “evidence.” The police frisked my home and Ishizawa’s but came up dry. No surprise.

With the seized articles in their hands, they now had to prepare a detailed written statement of what they had confiscated. A cumbersome process of identifying the shape and name of each of the seized articles, typing them, and checking/confirming the accuracy of description with me via the interpreter took place along with the questioning. It was almost midnight. Nivardo was anxious to go home and asked, “Shall we continue this tomorrow?” I spurned his proposal, “No, I don’t mind even if it takes till morning to sort things out. Please carry on.” From my experience of numerous all-night mah-jong games I knew that a decisive moment in any game would come at dawn. I was not such a bad mah-jong player, anyway.

As the dawn approached, Nivardo looked more exhausted and low-spirited than I was. So he called it a day, saying, “I want you to come over to the field site this afternoon ‘coz I need to check something about the seized property with you again.” At the sight of his despondentness, I realized the real meaning of this criminal investigation. Their plans must have been first to nab me red-handed at the tower site without evidence, and then to force me into confession, taking advantage of my confused state. Aha! The Brazilian police were bent on making arrests flagrante delicto.

Now I remembered. On my way to the tower site that morning, I was stopped at a checkpoint, and behind the traffic cops, I had seen those four guys who later came over to the tower. I was positive that they were there to learn what I looked like, and about 3 hours later, they rolled up to my research field, thinking that I must have collected some bugs by then. I now know that the Portuguese word “captura” means ‘capturing or collecting’; however, if I had unthinkingly replied “yes” when the TV camera operator barraged me with questions containing that word, I would have undoubtedly fallen into their sweet trap. I was sure that from the beginning they had planned on using that footage as evidence in the network news. Later I also learned that the TV news reports had shown some African-Brazilian attesting to having sold contraband insects to me. Malarkey! Of course, I knew of no such dude. Ironically, both my poor linguistic ability and the earlier-than-expected arrival of the Consul General, interpreter and lawyer so happened as to defeat the police’s wicked plot completely.

[TOP]

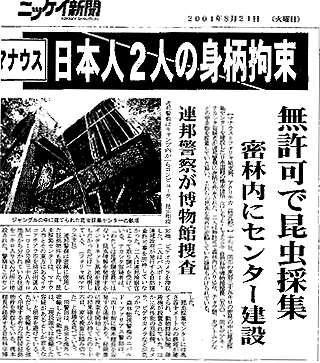

At around 10 o’clock in the morning the following day, August 17, Ishizawa came to my office with a load of major newspapers sold in the city. Sure enough, articles based solely on the police accounts of the incident made the headlines. A few days later, he told me that not only the vernacular newspapers but also a couple of Japanese papers published in Sao Paolo treated me like a criminal. Now I, and the Amazon Natural Science Museum, had earned quite a reputation as knaves across the society of Brazil, a country 24 times larger than Japan.

(While writing this, I ran into an old newspaper article on this incident in a Japanese English paper's website, the Japan Times, under the infamous title "Japanese held in Brazil over illegal trading insects" [Sunday, Aug 19, 2001]. Even after 8 years, my "wrongful act" is still being broadcast to the people of the world. Faugh! Thanks a lot.)

On the early afternoon of the same day, I went down to the tower site to help the police check on the equipment they had seized the previous day. The list included the main body of the airy tower in the jungle, an automatic temperature-measuring device, an automatic hygrometer, an automatic rain gauge and other one-of-a-kind materiel that I had contrived on my own. I normally left all these pieces of equipment at the site, so I had put up warning signs with a skull and crossbones saying “DANGER! HIGH VOLTAGE” at several locations around the tower. In general, Brazilians were not well versed in electricity. So, even such kindergarten-style gimmicks of mine had proven adequate as an insurance against thieves. Besides the police personnel, a staff person from the National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA- Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia http://www.inpa.gov.br/) was also present at the site. He was roving all over the place with an instrument in his hand that looked like a circuit tester, from which I gathered that he was an electrician. Before long he came over and asked me something, pointing at the signs. I pretended to have understood and said in Japanese, “All of ’em are dummy signs. Mere scarecrows.” Then he returned a knowing grin.

Having gone through the equipment list, there wasn’t much left for us to do at the site. That day I had driven my car to the police headquarters, and from there they took me to the site in their car. The return trip was the same procedure but in reverse order. They dropped me off downtown Manaus and I drove my car home. That was it. I really wondered what the previous day’s pother was all about. Nonpersisting police?

When I returned home, many of my friends around the country had come calling. When I answered those calls, everybody on the other side of the line got caught off guard and reacted identically, “Are you at large?” I don’t blame them. My case had been given prominent coverage in the newspapers across the towns and cities in the south too, not to mention Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. I was now perceived as a mini-celebrity.

Day three, August 18, passed without a single call from the police. But some of my friends in Japan who had finally learned about my ordeal gave me a call. It was around this time that I noticed strange things happening to my phones both at the museum and home. Every time I started speaking on the phone, there was some kind of annoying high-pitched noise and the sound volume of the receiver diminished, while the ensuing conversation suffered from a hum. The following day, I came across an interesting newspaper article on a mass arrest of a state legislator’s secretary and his cronies involved in a corruption case. The article contained a detailed account of the pains the law enforcement had to go through in the investigation. According to the report, the police revealed in boastful terms that they had played cat and mouse with the suspects and ‘eavesdropped’ on their home phones and mobile phones alike to round them up.

Aha, I see!

I decided never to talk about the “biopirataria” affairs on the phone, whether at home or at the museum.

Now what would I do? The case was still under investigation, but I was not indicted. The lawyer told me that there was no way to formulate any court tactics at this stage. The equipment at the site had been seized, and all of the specimens and other material stored in the museum’s warehouse had been carted away by the police. And I had to keep away from the phone at home. The situation left me at a loose end.

Some 40 Japanese corporations were currently up and doing in Manaus which was peopled by about 1,500 Japanese. There was a body called the Amazonas Japanese Chamber of Commerce, which had been formed for the purpose of fostering information exchange and friendly relations between those expatriate companies and the local Japanese business people. I was one of its members. Although the Chamber of Commerce had no direct implication with my museum’s activities or my business, it was a fun place to be for a person like me, because every once in a while whackily large hearted men or figures of fun --- normally, a rare breed in Japanese businesses --- somehow found their way into the Amazon basin, half a world away from home. And I was the one who would be amused at such people.

Now that things had come to this pass --- plus my lawyer suggested that maybe I should stay away from the museum for the time being, I decided to commute to the Chamber of Commerce every morning and spent my days reading novels by Shotaro Ikenami and Shuhei Fujisawa over coffee and chatting with fellow members and secretariats. Believe it or not, sociableness was part of my innate disposition (I hope you don’t let my taciturn bearing deceive you).

What really put me out of my misery was that the media reports on the incident did not hurt foot traffic at my museum. By the establishment’s nature, out-of-state Brazilians and people from other countries, including Japanese, accounted for a good part of the museum’s clientele. I was quite relieved that I was at least left with a way to earn my bread; I had to support a family of five including myself, my wife and three children, the oldest one being 19 years old then. A marked decline in the attendance figure would restrain my indulgence in Agrias butterflies and the tower.

After this, the police left me alone for a while, except for a couple of phone calls requesting me to submit the import certificate for the tower and the permits for the guns that were also part of the confiscated goods.

Then, at the end of August, I received a fax that summoned me to the city assembly. It said that they would hold a hearing to ‘take up angry shouts’ demanding that ‘a museum run by a suspect of insect smuggling shouldn’t be allowed to stay open and should be shuttered immediately.’

Impossible! Had I been indicted and found guilty on the case, I would have complied with such an appearance order all right, but in actuality I wasn’t even under arrest, let alone indictment. In the course of time, however, the city council seemed to have shelved their plan for good. It was a foregone conclusion, and I paused to realize that unlike in Japan, the unthinkable could happen here in Brazil. I wasn’t alone in my feelings of righteous indignation over injustice; later I was informed that the call for my summons was dispelled because some city council members who I knew personally had lodged a protest. My luck picked up once in a while; someone whispered in my ear that the ‘angry shouts’ had turned out to be concerted appeals by “five Brazilians including one of Japanese descent.”

Then, it suddenly flashed on me that they might have been the ones who gave the federal police a slanderous allegation of my involvement in smuggling with no supporting evidence. Seeing people visiting my museum just as before while I was enjoying my leisure time chewing the fat over coffee, they must have changed their mind and decided to use starvation tactics. Hmm, a likely scenario! But there was a Japanese-Brazilian involved. Why? I found myself at a loss.

As suggested by the title “The Japanese Were Called ‘Garantido’ in the Amazon” of a book written by a journalist (a friend of mine), Japanese were reputed to be highly reliable in Brazil (the Portuguese word ‘garantido’ means ‘guaranteed’, and represents the trustworthiness of the Japanese people as perceived by the non-Japanese locals). I wouldn’t like to think that any one of my fellow people assumed a role in the gang that was attacking me.

I admit that there was some rivalry among the insect buffs I knew, but I had no guesses about anybody who might hit that hard below the belt.

I wouldn’t get frightened of piranhas, candirus, tarantulas or vipers, but this time I was really disgusted by an enemy whose identity and behavior were unknown to me.

Therefore, I took several precautions to defend my security, I limited my means of transportation to a sturdy truck with the kangaroo bars, or bull bars, of Nakashita’s special make, and changed my traveling routes whenever leaving home, and shied away from going out by myself. They say that in Brazil you could even hire a hit man for a mere $3 grand. Brazilian-made Taurus handguns diverted to the black market by cops would cost you only 100 bucks a piece with 5 rounds.

[TOP]

September passed, then October. During that time I didn’t hear a word from the federal police. I was under suspicion of violating the Forest Development Protection Law and of illegal possession of firearms; they even cast their doubt on the money (about US$ 10,000) they found in my safe. I presented the gun permits and explained that the cash included my working capital and my wife’s nest egg. If they were still dissatisfied with my clarifications, why wouldn’t they file formal charges against me without further ado? I inquired of my lawyer for the current status of the police action; he said that the public prosecutor’s office was absent of any hint of having received papers on my case yet. Not surprising, because unlike their Japanese counterparts, public servants in Brazil, including law enforcement officers, would have no compunction about taking a leave of absence from office for as long as 45 days, even in the middle of their investigation. My phones kept producing the exotic whirs and hums as ever. Was it a sign of someone still working hard to get “enough evidence to indict me”?

More than six months went by without placing me under proper investigation. In the meantime, I was absorbed in reading at the Chamber of Commerce and sipping fine Brazilian coffee. In the evening, I would make a couple of phone calls to lure someone to take a meal with me. I don’t touch liquor. With my access to the tower being forbidden, I had some surplus of research budget. I would be better off being with my friends, rather than feeling bad about my ordeal in solitude. I cooked and played host every once in a while. Cooking was my favorite pursuit. I had several hundred dishes in my cooking repertoire, and could sing more than 1000 songs in karaoke. It seemed like a party every day.

Thus, I made quite a few new friends among Japanese and local Brazilians alike. It is not so difficult to enlarge the number of one’s friends down here. Then, some unthought-of things happened. I started receiving interesting information, though on a piecemeal basis, from my new amigos of various backgrounds.

Of particular interest to me was a lead that someone had heard a small group of researchers at the National Institute for Amazonian Research talking about their desire to jump a claim on my tower. That reminded me of the day after the search. One of the guys who came over to draw up a document for the items the police had confiscated was a researcher of the Entomology Section of INPA. I downgraded his presence because I thought the police had called him in as a specialist to make up for their lack of experience in the field they were dealing with. I also remembered that an INPA’s canopy researcher (Dr. N. H., a Japanese) had once dropped an envious sigh and said to me, “We want to have a tower like yours, but unfortunately it’s beyond our purse.” When I saw him again at a Japanese restaurant at a later date, he turned his face away from me. I thought it was strange. Could it be that a national laboratory dared to prey on an innocent private citizen with false accusations? No way!

INPA, founded in 1954, was the only national research institution working on studies of the Brazilian Amazon. Up until its inception, scholars had traveled up here all the way from Sao Paulo to do research on tropical Amazon biota. Back in those days, you wouldn’t be able to find a graduate-level biology laboratory anywhere other than in the state of Sao Paulo. Only a few universities, such as the Federal University of Parana, had a department of entomology. Probably feeling embarrassed about not having a decent laboratory in the Amazon --- a world-class trove of much coveted biologic resources, the government set up the National Institute for Amazonian Research. The problem was that post-war Brazil was in the midst of an economic boom, where a young researcher with a master’s degree in advanced research would easily get paid four times as much as average Japanese salarymen at the time. What’s worse, the city-bred, college-educated elites were so proud that they wouldn’t give a second glance to a backcountry position being offered in the Amazon. Though I don’t mean to sound presumptuous, it is really hard to say that the level of “human resources” who applied for such positions in the days of a sellers’ labor market was excellent anyway you look at it, even by the standard of chronically job-scarce entomologists.

But at the same time, INPA had accomplished reasonably good results in botanical researches, and had been the one and only national institute for Amazonian research ever since the Environmental Summit in 1992, which touched off the Brazilian government’s ban on research activities in Amazonia by foreign nationals in view of the protection of its biologic resources --- a virtual closure of the area to the world research community. Those foreign laboratories or universities wishing to do research on the Amazonian biota must turn to INPA first for counsel and then would be only allowed to conduct “joint studies” with them. Having thus established its presence, INPA had become the face of Amazon rainforest.

So, how could I have even thought of some doctoral-level researchers of such a magisterial institution daring to bolt up and make me a scapegoat even if my tower had been an object of envy to them? Perhaps, it was just a fancy entertained by a person whose academic background fell short to match better-educated entomologists.

In March 2002, a change in institute head was announced. Prior to the formal assumption of office by the new president, a friend of mine, who happened to be acquainted with him, threw a Sukiyaki party for him. On that occasion, I ran into that Dr. N.H. and had a little chat with him again. Our conversation moved naturally to the police investigation and the tower. Taking this opportunity, I asked him, “I was told that your institution would be in charge of appraisal of the specimens the federal police seized from my museum. But it’s such a problem that no written expert opinion is available after six months. Could you check when the police might receive that evidence from your organization?” In Brazil, it wasn’t uncommon that a stand talking at a party like this was much more efficient in solving a problem than bureaucratic procedures. Then, I made a casual remark to Dr. N.H., “That tower. I wonder how longer the federal police will keep it seized. What a waste. You could take it anywhere in the Amazon if you unscrewed the anchor bolts at the base and hauled it out of the ground with a crane. Easy.”

Then, about two weeks later, on April 7, one of my Japanese acquaintances living in the neighborhood of the forest where my tower stood conveyed astounding news to me. He told me that my tower was gone! The forest was part of a suburban Japanese colony called “Efigenio de Sales”, where most families were poultry farmers, and I knew every one of them. The newshawk was one of those farmers, and he said, “A few days ago, I had noticed in passing that your gate was broken. So I went back there today only to find that your tower was gone.” He told me that my meteorological equipment and tent were missing too.

I was quick to take my lawyer and head for the federal police headquarters to find out what was going on. Upon receiving my report, one of the inspectors in charge presented a piece of paper and said, “Oh, yes. There was a petition from INPA for relocating the tower. So, we gave them a go-ahead.” The paper contained some statements to the effect that: “i) the motor and some sensors had been lost; ii) INPA would not be able to fulfill its custodial responsibility, as long as the tower remained where it was; iii) therefore, INPA thereby requested permission to relocate the tower to its own research site; iv) the landlord of the current tower site complained that the presence of the tower had been causing inconvenience to him; and v) all of the expenses incurred in the proposed relocation would be born by INPA.” I had stayed away from the tower ever since the police raid. There was a traffic checkpoint set up on the way to my tower site; if I walked into the vicinity of the tower, the police woudl be capable of accusing me of “destroying evidence”. I knew that much.

According to Brazilian law, I was required to obtain a leave of court for traveling out of the country, and police permission for leaving the city for longer than a week. Although trips to suburbs of Manaus were not subject to such procedural restrictions, I held back my desire to go see my friends in outer suburbs. As they say, it’s better to be safe than sorry. But the landlord of the site of my tower in Efigenio de Sales was a successful immigrant farmer and, moreover, a friend of mine. The tower stood in a corner of his extensive fields; so, there was no chance that the tower or my activity around it could cause him any “inconvenience” whatsoever under any circumstances. In fact, INPA themselves caused more than mere “inconvenience”, because they had taken the liberty of breaking the gate to carry the tower out of the site without the landlord’s permission. So I asked my friends in the colony to find out if there was anybody who had witnessed the relocation scene. Then, a few days later, my search yielded an interesting piece of information that someone had seen “two apparently Japanese persons in a red Fiat watching over people working on the site.” A red Fiat! Dr. N.H. of INPA, whom I had told about the tower at the party, owned one. Was it just a coincidence?

Nine moths after the blessed police raid, I finally had room to breathe and figure things out with a clear head. I got around to reviewing newspaper articles on the case and comments of the people involved that had escaped my attention in the aftermath of the police raid. A few of my friends were of substantial help in the tedious task to go over all the relevant Brazilian newspaper articles written in Portuguese. One article written about 10 days after the incident came to my attention. It contained a comment by Dr. Kerr, then head of INPA.

Dr. Kerr was a naturalized Swiss-Brazilian and an entomologist specializing in bees, and his standing as head of INPA was comparable to that of the president of a national university. However, a figure of such social importance as he was, Dr. Kerr commented without scruple, “Hashimoto will be convicted, and this tower will come into our possession sooner or later.” Hey, wait a minute. At that point in time, as far as my case was concerned, INPA was not supposed to be anything more than an “appraiser of impounded articles” at most. It was so absurd for the head of such an institution to say boastfully before newspaper reporters that a material possession of somebody who had not been indicted, or even arrested, for that matter, would come into “their possession”. Such a comment would never have popped out of his mouth unless he had had a great deal of confidence in his plan.

Then, I was flabbergasted by the content of the “written expert opinion” submitted by INPA and equally by a report on said written opinion in a local newspaper published several days after the Sukiyaki party. The article decisively stated, though without showing the evidence, that the specimens confiscated from my museum “represented all but illegal possession for commercial purposes and were construed as intended for illicit sales.” Furthermore, the article added, “Hashimoto is under suspicion that he may have had linkages with the recently arrested smuggling ring.” Faugh! The ‘smuggling ring’ mentioned in the article referred to a group of 6 Swiss nationals who were arrested on suspicion of insect smuggling at Manaus Airport on the day of that Sukiyaki party. The article also contained an allegation made by an INPA guy named Wellington to the effect that I had something to do with said smuggling gang. It would seem that INPA and the press sided with each other.

According to Brazilian law, the custodian of my tower would be allowed to put it to his own use as long as he came up with some proper pretext, such as “for the purpose of performance test on the tower.” At this moment, something told me that my tower might have been the intended quarry of a usurping plot from the beginning, and that the involvement of a national research institution, INPA, in such a plot might not be a remote possibility.

[TOP]

Though I am a good-for-nothing insect guy, I can hang on and be patient. When a blood-hungry mosquito keeps buzzing around me in bed, I don’t need to go get a mosquito-coil, insecticide spray or anything of that sort. I would stay put, follow its movements and whereabouts attentively, and finish it with a single slap. This mastery of mosquito destruction impresses people who see me demonstrating it. Well, there is no difficulty involved, actually; all it requires is to know the whereabouts and behavior of the mosquito. Oh, I am also good at finding a tiny mimicking bug perching on a leaf. I am confident about staying put for ever if I find one, even if a wasp rests on me. The true culprits who had designs upon my tower and museum were unknown yet. All I could do at the moment was just sit tight and show great patience. Yes, that was up to my line.

Under Brazilian law, the investigation of a criminal case shall be completed within 90 days; at least, the text says so. But my case had been left open without progress for over 6 months, during which I was never placed under investigation, except for the questioning on the very first day of the incident. According to my lawyer, when the first 90-day term was up, the federal police prolonged it for another 90 days on the grounds that “INPA’s written opinion had not been available yet.” Then, another 90-day extension on the pretext that “evidence for alleged smuggling by Hashimoto at the border with Columbia was under scrutiny”; another 60-day extension on the excuse of “suspicion of tax-evasion”; and finally, a 30-day extension on the grounds that Nivardo was transferred somewhere else, and his successor, a female ‘delegada’, took a leave of absence for her operation. By this time, it had already been a year and a half since the first raid on my tower.

It was in December 2002 that some changes came out on the tower site, at last. One of my acquaintances in the Japanese colony gave me a call to report that the electric transformer, which had been left behind when the tower was demobilized, was gone. In a stroke of good fortune, one of the guys in the neighborhood, who was an ex-police officer, had witnessed a Toyota pickup truck that carried off the transformer, and jotted down the license plate number. I filed, through my lawyer, a robbery report with the Amazonas Provincial Police Department that handled property crimes like this, rather than with the federal police.

As a result, it shortly turned out that the owner of the pickup truck was a man by the name of Rafael, who was one of the staff of INPA and the head of its invertebrate (i.e. insects) division. Later I was informed that in response to a police inquiry, Rafael had reported himself to the Provincial Police and presented INPA’s written statement to the effect that they had displaced the transformer for “preservation of evidence”. It was unknown why the INPA heavyweight came to pick up the transformer a good eight months after the tower was carried away. I still had to take a wait-and-see attitude at this stage; however, given the linkages suggested by the red Fiat and this Toyota pickup, it seemed more than probable to me that the executives and researchers at INPA harbored an extraordinary interest in this particular tower. And oddly enough, documents related to the investigation were subsequently lost. Not once but 'TWICE' They remain missing to this date.

While there is a stipulation to limit the term of investigation on a criminal case to 90 days, the case shall be built and the suspect be prosecuted normally within a period of two years. Now it was almost into the summer of 2003. And it had been nearly two years since the federal police yanked me from the tower on August 16, 2001. They had left me up in the air without a hint of placing me under investigation of any sort. So it was only natural for me to expect to see the light at the end of the tunnel at this point. However, my lawyer, who went to get the feel of how things were going at the federal police headquarters, came back with an unexpected report. He quoted the head of the squad saying, “Actually, we have finished our investigation on this case and given up on further investigation, as far as we are concerned. But some people in Brazilia are still making a fuss about something. So, would you wait a little longer?”

“Brazilia” refered to the federal government, of course. In July 2000, a year before the seizure of my tower, some National Congress members on the environmental affairs committee had come to visit the Amazon. A newspaper article on their visit at that time trumpeted that the mission was informed that INPA had been “currently investigating a heinous contraband trader by the name of Hashimoto.” INPA was not even an investigative organization, but they obviously looked on me as an enemy or something.

Just around that time, environmental nationalism was taking root in Brazil and given big write-ups in the newspapers carrying articles to the effect that “Amazon forest gene resources were hemorrhaging, and the daily economic loss would amount to US$1.6 million.” It would seem that I was being made to be a fat target in their campaign against “gene hemorrhages.” To my sorrow, however, I was in a delicate position as an immigrant, who was always at a risk of being called “persona non grata” whenever he expressed his grievance about the system of the host country. At the height of the resource-environmental nationalism, I was forced to remain silent. Nationalism in every country needs to find a vent. The congress, police and media --- everybody was looking for a scapegoat. I was just like a goat that got stung on its nose by a wasp, but I took it on the nose without a single bleat.

Toward the end of 2003, freak events happened one after another. On December 2, some of my tax documents disappeared from a room that I had rented in the Japanese Association building. Among tens of pages of documents, only a few important sheets had gone while I was out of the room for 10 minutes or so to put out the garbage. Then, a week later some people from the national taxation bureau visited me for inspections. I was forced to pay an amount of more than US$ 10,000 because of the fact that those essential documents were missing. It was a heavy blow to me. As far as thefts are concerned, it is the “aggrieved party that is perceived as being at fault” here in Brazil. The tax bureau people were sympathetic, but that’s probably because they knew that I would have to pay anyway.

But interestingly, I subsequently learned that there was an unidentified man who lodged information about alleged tax evasion against me at precisely the same time as this theft case. Realizing that the federal police was unable to build a case on “smuggling”, the invisible enemy seemed to have thought that there might be more chances to indict me for “tax evasion”. But “tax evasion” was not within the federal police’s jurisdiction but the tax office’s. And the taxation authorities would not challenge my activities as long as taxes are paid. Upon confirming that I had paid the first “installment” of tax payment, they immediately issued a certificate to the effect that I was free from defect in terms of the tax code. Yes, I was a top-drawer customer for them.

On September 22, 2004, two weeks after I had finished paying off all the tax installments, a triad of robbers broke into my museum during my absence, and tied up my wife and gagged her with an adhesive packing tape, and burgled a safe in my office. I would have had my tax certificates stolen again had I been unvigilant. But I had learned a lesson by that time and resited all the important documents elsewhere. Then, a week later, as if accidentally, there was a summons, this time, from the federal police, requesting my clarifications over things related to tax. Triumphantly nodding to myself, I made a whole bunch of copies of the tax documents at a notary public office and submitted them to the police at the drop of a hat.

Oh, what happened to my wife? She was a stouthearted woman. Far from being shocked by the incident, she was busy sending e-mail to her friends in Japan, funnily reciting her yarn. What would you expect of a woman who married a guy who was branded as queer fish in the Amazon! Honestly, I would have been in trouble if she had said, between her sobs, “I’m fed up! I’m going back to Japan.” I even thought of praising her guts, but I decided not to, because I remembered Shotaro Ikenami, my favorite novelist, having one of the characters in his novel utter, “Never praise up your wife, or she would get cocky to the end of the world.” Then, my wife made a rather hurtful remark, “I don’t want you to cross over to the other side now, because I would be left with that silly tower that would be good for nothing except as a bungee jump platform. So, I want you to get hold of yourself.” I was glad I didn’t compliment her on anything.

Besides those incidents with lots of question marks, records of investigation and certificates considered favorable to me were repeatedly lost within the federal police. For a short time I had a hard time believing. But my amigos told me with a straight face that it was a way of life here. So, I ran to the notary office to make a plurality of copies of every document that could be of any importance to me. The fed kept issuing orders requesting me to submit various documents, such as tax documents, gun registration and what not, one after another, as if they were playing a game of emotional harassment. But every time there was a police request for submission of something, I responded to it with a hair-trigger delivery. Before long, loss of documents of this sort was suddenly done away with.

A young female ‘delegada’ (chief inspector), who was an out-of-stater (I can’t remember any more how many predecessors there were in this position before her), laughingly suggested that she had put all the documents related to this case in sealed plastic bags and had them numbered serially. She was no fool. She knew exactly what sort of thing her ‘amigos’ would do to them.

In time, I was informed that the indictment limit of my case had been prolonged for another 2 years for some reason or other. I didn’t understand what made such an extension possible. My lawyer’s accounts didn’t explain away the situation either. It seemed that my poor Portuguese wasn’t the only reason. I decided to hire a new lawyer in the fall of 2003. Bingo! My decision would turn out to be a right one soon.

[TOP]

It was through the introduction of one of my ‘amigos’ that I got to know my new lawyer, Mr. Washington. He was an ex-inspector of the Amazonas Provincial Police, having a track record of being appointed as an instructor to train ‘delegados’ at the senior police academy in Brazilia. When he reached the pensionable age, he retired from police and began the practice of law. I was also told that most of the police ‘delegados/delegadas’ in the Manaus area were either his ex-pupils or subordinates.

Unlike most Brazilians, he was a lean man and had an appearance of a college professor with a searching look and a hooked nose. He spoke coherently and often cut me short and said repeatedly and petulantly, “Think calmly and speak more logically.” He was sharply dressed in his suits with a pair of dark Rayban-type sunglasses, which he would never forget to wear to hide his eye movement --- an ingrained habit from the days of his police service. I could immediately tell that he was a very studious person. Although he was a criminal attorney, he had already been well versed in the forest protection law and environmental issues when we first met with each other.

My legal counsel moved very quickly to pinpoint his finger on a Brazilian named Estinger as the man who dropped a dime on me. Estinger had met the commissioner of the federal police several months before the raid on my tower. At that time, he was a staff personnel of the Canopy section at INPA. Not only that, he was a ‘bem amigo’ (buddy-boy) of Rafael, yes, the guy who took my transformer away in his Toyota pickup truck. They were also drinking pals who had a drink together almost every other day. The competent lawyer even checked up that Estinger had frequented the federal tax office and prodded them to lay an accusation on me.

We also learned that when Estinger was transferred to the Amazon Protection System (SIPAM- Sistema de Proteção da Amazônia), he used his administrative authority to cause the border patrol to look for any evidence that would suggest my potential involvement in smuggling near the border with Columbia. I see. He was the one who was responsible for the actual execution of the crime that had tormented me for such a long time. But how could my new lawyer assemble such an intricate jigsaw puzzle in such a short period of time? It was nothing short of a mystery, because despite years of efforts by my former lawyer, the puzzle had appeared simply unsolvable to us. Washington said confidently, “Every culture has its own way of doing things.” He was an expensive lawyer, but I paid the amount (full amount, not a cent less) claimed for his service without a murmur.

Prior to those revelations, there was one case (and the only case) that the federal police succeeded in building and sending to court, where I was made to sit on the dock as a defendant. According to the charge sheet, they accused me of having stolen a motor and meteorological sensor, both of which were accessories for MY tower. Those were the items that had been left behind at the site for some reason or other when the INPA people removed my tower. And the written accusation stated that those accessories subsequently went missing, and I was charged in stealing them! It was too silly for words, and at first I couldn’t believe it because it would have been unthinkable in Japan. The charge had been brought to a ‘delegado’, and was established as a completely separate case, in which where I was indicted. Among the charges they hurled at me, this was the only one that made it to court.

The first trial hearing was held in June 2005, I attended court with my lawyer, Washington. The judge suggested an “out-of-court settlement” as soon as he sat on the bench. “You can’t be serious, your honor!” I shouted in my head. This was a system called ‘acorda’ in Portuguese where the judge would give a suspended sentence in exchange for the defendant’s confession to a crime, or something like that. But this system was originally intended for application to those defendants of minor crimes that were unable to pay legal bills.

I refused to accept his proposition. Come on. Someone was calling me a thief! I had never set my foot on the tower site since that police raid, not once. So, why would I have to succumb to some person who had falsely accused me, and settle the case out of court? Don’t mix my case with a misdemeanor like a traffic offense. So, I doggedly requested a formal trial.

Institutional constraints shielded the identity of the accuser from the accused. However, my lawyer found out, as quick as lightning, who they were. One was Rafael, head of the Entomology division at INPA, and another man named Sady, the black guy who attested to having sold insects to me in the August 16 TV news report. In the course of preparing for the formal trial, Washington also discovered that I had been classified under the category of “ex-convicts” in the provincial-level criminal record database. The label of being an “ex-convict” by itself would count against me in court. I immediately lodged a protest; then, the police corrected themselves without much resistance, saying “It was just an ‘input mistake’”. Yeah, somebody’s ‘amigo’ must have helped to cause that input mistake too.

The deliberation of the formal trial was terminated after the first round; because when the judge asked if Rafael and Sady would testify that I had stolen the tower accessories, they respectively returned a stupid answer, “I am not sure if Hashimoto was a culprit, but those items were gone for sure.” Wow, the guys who brought a charge against me negated the very ground of the charge! I was quite positive that they must have been flustered like hell when they saw the competent Washington sitting at the counsel table. They must have underestimated that they’d be able to get the better of me easily because up until then, I had not gone on the counteroffensive in my smuggling case, at least on the surface. In this strange turn of events, the prosecutor in charge had little choice but to smile bitterly.

Washington had been prepared to sue for slander just in case the witnesses testified against me without evidence; he even had in store a police witness who would testify that I had never visited the tower site since the incident. In Brazil, slander was not just a minor pecuniary offense but a felony charge subject to a prison sentence. After the first trial, the case was out of court. I naturally expected that a determination of my innocence would be made soon.

However, as far as this criminal action was concerned, the end-all sentence was not given until long afterward on the grounds that “since this motor/sensor theft case was related to the smuggling case; there would be no sentence delivered before that case came to conclusion.” They first indicted me in a "separate action" but then when they had to decide the case, the court was reluctant to hand me a favorable ruling. What a nonsense!

After 4 years from the incident occurrence, my “smuggling case” was still a “live case”. The term of criminal investigation for my case was initially “2 years” and subsequently prolonged to 4 years. While now we were into the fifth year of the prolonged investigation, the federal police showed little intension of wrapping it up. In answer to our enquiry as to the reason for delay, they said, “Because the motor/sensor theft case hasn't been closed but is still on trial.”

It was a typical case of administrative “slow-down”, or “sabotage”. It was like the federal police was saying, “We are getting no chickens because we have no eggs,” while the court was saying, “We are getting no eggs because there is no chicken available.” But I stayed cool just as those cyanobacteria living on a glacier. By this time, I had built a good stock of ‘amigos’ who were not only sympathetic with me but also brought in all kinds of information that helped me see how things were going within INPA. Apparently, not all INPA staff ware breathing on my neck. Several evidences pointed to a likelihood of “joint action” between their Entomology section and the Canopy section, which had a hankering for a decent tower. Though this trial for theft allegation was a total nonsense in itself, we thought we should be satisfied at this stage with what we had found out about the identity of our enemies.

Another year passed. It was August of 2006. I had been beleaguered by this seemingly endless battle already for 5 years, during which the federal police had not added a single piece of evidence for the ‘smuggling allegation’. And I was told that INPA kept doing their “research activities” using MY tower without even getting embarrassed. The code of ethics of academic circles around the world usually rejects research papers containing findings obtained by means of illicitly acquired equipment and materials. INPA, however, was callous to a potential forfeiture of their academic credit, because the use of my tower by its custodian, INPA, was not illegal under Brazilian law. I wonder if you remember that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2007 was shared between Albert Arnold (Al) Gore Jr. and 530 scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The reason for the scientists winning the award was attributed to their presenting of scientific data instrumental in assessing the global environment. There was a hanging doubt in my mind that maybe, one percent or so (too much or too little?) of the meteorological data on the Amazon presented by the Brazilian scientists might have been collected by INPA using MY tower and meteorological equipment.

The stock of my enemies’ ammunition seemed to be running low eventually; there had been no discernible moves by them to mess with me for the past few months. Still, I wouldn’t let my guard down yet. I changed my routes every time I went out in my truck, checked to see that there were no bombs planted in my truck, and never talked about anything related to the case on my phones, which had stopped making those whirs and hums for some time. These behavioral patterns had become my second nature. During all these years I had not talked much about the case at home, so I was not aware of how much my kids knew about it. But my 24-year-old son, who was 19 at the time of the incident, now aided my work at the museum. I had initiated him into most of my secrets and know-how on the water temperature/chemistry control and the like for my pirarucu aquarium. My daughter was studying biology at the National Amazon University. They would be able to survive even if something deprived me of being able to provide support for them.

I thought it was time for me to fight back.

[TOP]

The state-level district court was low in morale and effectiveness. I didn’t like to think that the court too might be infested with my enemies’ amigos, but it was evident that the court’s current procrastination would only do good to my enemies who were in a position to use the tower as much as they wished.

But come to think of it, there was no way for me to win acquittal in the “smuggling allegation” in which I had not been even indicted in the first place. So Washington thought out a clever plan to appeal directly to the High Court in Brazilia, denouncing the current procrastination on the part of the federal police and the local court as illegal.

My lawyer thought that while the joint-effort sabotage between the federal police and the federal district court might work effectively at the state level, they would have no means of wielding their influence over a trial at the High Court in Brazilia or even knowing about such a trial for a while.

This surprise attack turned out to be a highly successful maneuver.

It was in November 2006 that we sent out our documents to file a complaint with the high court. As a result, decision was reached in February the following year. Whew! That was a miraculously fast decision for a Brazilian court. We gave a big hand to the Ayrton Senna-like court not only for their swiftness in court procedures but equally for their truly ‘judicial’ mind. The sentence read, “The court construes the present matter as a meaninglessly procrastinated investigation and hereby orders a prompt termination of said investigation.” It was a consensual decision reached by three judges. Three to nothing. Yes, it was a hat trick.

After a 20-day grievance-filing period, the court ruling was gazetted in mid-March, and accepted as final. According to Washington, since the decision was reached by unanimous consent of three judges, it was extremely unlikely that the court ruling would be overturned even if the federal police in Manaus made a demur. He shook my hand and said confidently, “It’s a complete victory, Hashimoto.” I was glad that justice wasn’t done away with altogether in the Brazilian judiciary. He also told me that the determining factor in reaching the court decision was the fact that federal police failed to add any documentary evidence in the past year after having prolonged the 2-year original term of investigation to 4 years. I was quite relieved to know that even that last one year I spent feeling empty proved to be a somewhat worthwhile investment. There was no avenue for this particular case to be heard by Supreme Court. So, that was it.

Throughout the past years Nakashita had, every now and then, vented his grievances on me, saying, “Why do you let them beat us down like this? Are you going to sit still forever?” It wasn’t easy for me to keep my cool, but every time I would tell him just how I felt. “Don’t forget that we are immigrants in this country. The government can always resort to a plea of ‘if you have a gripe so unbearable about our country, why don’t you go back where you came from.’ So we have no choice but to wait till the time is ripe. But I’m sure there must be decent humans in this country too, and I would like to believe that not all of the judiciary system is corrupt.” I am glad that I was right. Directly following this ruling in Brazilia, the district court in Manaus was quick to render judgment of acquittal of the “motor/sensor theft” charge, which had been left up in the air for so long because of that “which-comes-first-chicken-or-egg” theory. For some reason, I dreamed up a ready-to-be-culled chicken (the court) that at long last produced a much-needed egg when the party was almost over. Thanks for the effort.

That said, it still took another full year before I actually claimed back my tower.

The court order issued in Brazilia required that all the investigations be terminated inasmuch as they related to the “smuggling” and “tax evasion” allegations. However, the tower and other related items remained in custody because they pertained to “forest development protection law” and, therefore, fell under the jurisdiction of the environment court set up within the district court of Manaus, which meant that those items would remain in custody for “investigation of yet another case”. How could they call it a ‘case’ while I was not even indicted in that case (whatever that was) either?

Trials at the so-called “environment court” of the state were held only a few times a year with a total of more than 5 months of intervening idle periods including extended leaves/absences of the judge. It was only in January 2008 that the district court’s environment court began its first trial based on the dusted-off documents, which had been tucked away and had finally made it to where they should belong. Then, there were some more discussions on whether or not the ‘case’ should require deliberations; and in May 2008, after coming to a conclusion that “the tower pertaining to the present matter should be returned to its original owner,” the judge and the prosecution signed a release order. I was really grateful to my lawyer Washington. Without his spectacular professionalism, the investigation documents would have been mothballed somewhere to this date. It appeared that the district court still operated under the 19th-century mentality.

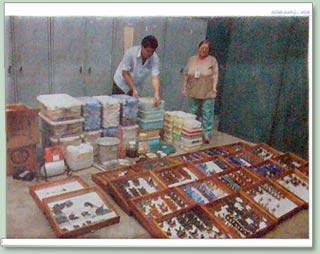

Shown below is a photo in an article of a local Brazilian newspaper, Em Tempo (picture left). The headlines said, “Law’s Delay Causes Return of Equipment and 4000 Insects to Biopiracy Suspect in the Amazon”

In retrospect, it all started out with an investigation of a “smuggling charge”, which was groundless in the first place, and the ‘charge’ was transformed into a “tax evasion charge” along with a ‘suspicion’ of illicit possession of the firearms that were seized in the process of the “smuggling charge” (all the permits I submitted were in good order, but those documents were lost repeatedly but every time I resubmitted replacement copies). Then when I sought the return of the tower seized on the “smuggling charge”, it was changed into yet another separate “charge”. It was a ‘wonder-ful’ bureaucracy that kept seizing the wrongfully confiscated articles belonging to me who was not even indicted in any of the ‘charges’. Since they were able to prolong their investigations for 7 years on the pretext of mere "suspicions", they would be capable of cooking up a charge against me of an “attempt to endanger world peace by practicing black magic.”

Shown right is a photo in an article of a local Brazilian newspaper, Em Tempo. The headlines said, "Law’s Delay Causes Return of Equipment and 4000 Insects to Biopiracy Suspect in the Amazon

The local Manaus newspaper article reporting the return of the specimens, which had been seized by the federal police in August 2001 and which INPA had kept for the purpose of ‘appraising’ and ‘spreading of the wings’. The photo shows butterflies in the cabinets, the spreading of which had been conducted by INPA --- action purported to be for ‘appraisal purposes’. Forty percent of them were in damaged condition. (Article in a local newspaper dated June 19, 2008)

Even upon receipt of the order to return the tower to me, INPA still demanded an “investigation period of another 90 days” without scruple. When I turned it down as a matter of course, they attempted to procrastinate further at this last moment on the ground of absence of their lawyer. They were not at all game to return my tower, and they seemed determined to play this game with me throughout the rest of my life. I stopped crying over my ordeal and decided to play it with a smile (or a laugh, maybe).

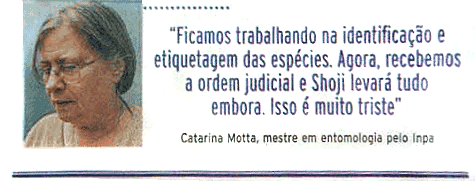

In the end the specimen cabinets that they had long kept in “their custody” were finally returned to me on June 18, 2008. It was more than probable that their lawyer was sensible enough to anticipate that they might get sued if they kept bidding defiance to the formal orders by the federal High Court and state district court. A male staff member of INPA’s entomology section witnessed the return and made a grandstand performance for the TV camera with his arms spread wide open to block the transition of the specimen cabinets. Another woman, his boss, stepped in and shouted, “We’re not returning these cabinets to you!” The following day, a local newspaper carried a full-page article quoting the INPA curator saying, “Hashimoto has not been cleared of his charges yet. It’s very sad that we have to return the specimens to a suspect.”

A specimen of my butterfly which was badly spread by the INPA entomology section. Note the paraffin paper pasted over the wings. Even a primary schooler would avert such a sloppy job.

The local paper, El Tempo, reporting the incident.

Miss Catarina Motta, an INPA researcher with a master degree in entomology, lamenting, “I’ve engaged in identifying and labeling those specimens all these years, but now the court has ordered me to give them up. I feel very sad.”

An Agrias butterfly, on which Ms. Motta performed the spreading of the wings. According to INPA, this is a butterfly worth a few thousand dollars, but it’s in a decrepit state. This particular specimen was originally flawless when it was in ‘my’ cusdoty.

However, I heard through the grapevine that overly one-sided as it was, the newspaper article had been toned down at the direction of somebody in the management, who learned that Washington was my legal counsel. The returned specimens were in dreadful shape; they could hardly be expected to have been “in custody” of professionals. At the sight of the trampled specimens, I became suddenly aware that INPA researchers desperately needed to keep my butterflies, because they, professional entomologists, didn’t even have the technique for spreading butterflies that would be good enough to pass for a level of proficiency required for summer homework of an elementary or junior-high boy in Japan. If you don’t believe me, please take a look at the photos shown below. I’ll leave it up to your own judgments.

In an interview with the abovementioned newspaper, the person in charge of “preparing specimens for appraisal” at INPA, Ms. Catarina Motta, cried crocodile tears, “I’ve worked really hard to identify all these specimens, but now I’m ordered to give them up. I am so sad.” Give me a break, Ms. Motta. Isn’t it me who should be sad, because it is me who got HIS specimens ruined?

Another specimen of swallowtail butterfly, that Ms. Catarina Motta, Entomology section at INPA, botched in her spreading of the wings. I have no idea what she had to do to make such an impossible example of disfigured specimen.

On the same day, I went to see my tower on INPA’s research field. It was a reunion after 7 years. The tower was just as important to me as Ichiro’s baseball bat was to him. It was the superb result of excellent workmanship by Aichi Tower Manufacturing Co., Ltd. The president of the company, Mr. Horibe, had taken the trouble to come twice all the way from Japan to do preparation and installation work himself. But the once majestic architecture was now a dilapidated structure with some of the beams being bent and the switchboard messed up after long years of unmanaged use and modification. The sensors, which were instrumental in securing safety, were in complete dysfunction due to tinkering; the pulleys suspending the elevator exhibited excessively uneven wears; and the structure suffered multiple traces of God-knows-what incisions. A few more months of such neglected use would have definitely turned the tower into a mere heap of scrap iron. That was the reality of what they called “custody.” I apologized to the tower, silently whispering, “I’m really sorry for this. I promise to put you back the way you were.” Since it was INPA that had taken the liberty of relocating the tower, they were supposed to be responsible for returning the tower at their own expense; however, I was disinclined to leave the tower there even a single day longer. So, I hired a crane vehicle at my own expense and carried the tower to the yard of my museum on June 23. I felt as if I had managed to rescue an abducted daughter from captivity at long last.

INPA’s harassment still persisted. I was supposed to leave for Japan before the end of June to procure a new telemetry system and some components necessary to restore my tower, as well as to visit my friends who had cared much about me. But when I was ready to leave, the vice president of INPA filed a suit against me with the state’s district court, claiming that I was not yet cleared of my charges, so all those specimens should be put back in their custody. Whereas the local newspaper had given me the cold shoulder (very cold, below zero!) when the court gave the ruling in favor of me, they devoted a whole page to a write-up on this occasion, reporting “INPA seeks the return of the specimens on the grounds that Hashimoto has not yet been acquitted of his other charges; he is still under suspicion.” But Washington, my legal counsel, said, “They’re just crying sour grapes. Don’t worry. I’ll take care of it. You just leave for Japan and have a good time over there. OK?” and gave me an encouraging smile.

Telltale evidence of 7 years and 11 months of neglected use. The dented tower was a sickly likeness of my dream and honor.

A specimen of Comma (butterfly). Another botch of Ms. Catarina Motta, Entomology section at INPA. Note the patching in the lower left corner.

The war seems far from over, however. For the past 8 years, I’ve been forced to waste precious time of the last years of my life and to use up all the money I saved for research to pay legal fees, and now I am left with a large accumulation of debts. But I am more than happy to have been granted so much support by so many friends and amigos in coping with my ordeal. Our steady effort to reveal the real identity of our enemy has paid off to a considerable extent.

I guess I have been victimized as an object of willful wrongdoing not by the entire INPA but by a handful of its corrupt staff who got their lines crossed, thinking that this ‘back-country’ of the Brazilian Amazon would obey their thought anyway they wanted, just like in the chaotic days of the nation’s military government some time ago. In Brazil, there is a law called “usa campeão” which allows a squatter having occupied or seized a land lot for a certain fixed period to be granted its private ownership. This system was originally instituted with a view to promoting the development of the nation’s vast terrain; however, it’s been plagued by crimes committed by those taking advantage of loopholes in the law. There are even professional crime groups specializing in this area. Willful misconduct of this particular nature is referred to as “invasão” (literally, ‘invasion’ in English). Every once in a while, there occur incidents where Japanese corporations or farmers in Brazil get their property lined up in the sight of such malefactors. And it is evident that my tower and specimens were targeted for such “invasão”. But times have changed. Now, at a time when the global environment has become a major issue, the study of Amazon is drawing a whole lot of attention and interest from all over the world. It is my belief that giving a loose rein to the domineering “Bio Mafia” announcing themselves as ‘researchers’ in the real Mecca for environmental research will only do disservice to the nature of my beloved Brazil as well as to the no-nonsense biology students including those at INPA. Otherwise, the Amazon will have no future.

I haven’t squashed the blood-bloated “mosquitos” yet!

[TOP]